On the southwestern tip of the island of Java, where the vast expanse of the Indian Ocean and equatorial waters of Sunda straits merge, is one of Indonesia’s paramount national parks, UJUNGKULON.

On the southwestern tip of the island of Java, where the vast expanse of the Indian Ocean and equatorial waters of Sunda straits merge, is one of Indonesia’s paramount national parks, UJUNGKULON.

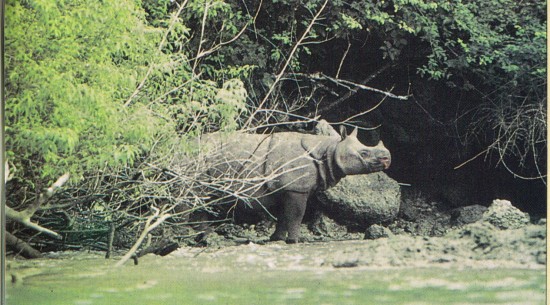

Rich in wildlife and forests, noted for its charm and diversity, it is the home of the highly endangered Javan rhinoceros and bestowed with the status of World Heritage (Natural) Site. Ujungkulon, which means West Point (Sundanese), possesses an exceptional profile of Indonesia’s wilderness from forested mountain rangers to coral seas. What makes it even more remarkable is that the park remains a pristine heaven of nature, on Java, one of the most densely populated islands on Earth.

In earlier centuries when the population was small and the forests were large, the people of the land lived with deep respect for the forest and its wildlife. Then began a two-century long struggle between humankind and nature.

The world first became aware of the natural treasures of Ujung Kulon in the 1820’s when botanist began venturing onto the peninsula to collect exotic tropical specimens. This was a time of colonial expansion and exploration and by the middle of the century; expeditions from the organization for Scientific Research in the Netherlands Indies drew attention to its unusual richness and scientific importance.

They wrote of the Peucang Island area in 1853: “Beautiful and safe bays… fertile soil… a wealth of timber for ship and shore… a splendid situation for commerce… the seed for a new Singapore.” Despite their recommendation to exploit the park’s resources, and fortunately for the future generations, nothing came of developing the region.

They wrote of the Peucang Island area in 1853: “Beautiful and safe bays… fertile soil… a wealth of timber for ship and shore… a splendid situation for commerce… the seed for a new Singapore.” Despite their recommendation to exploit the park’s resources, and fortunately for the future generations, nothing came of developing the region.

Thirty years later in August 1883, nature intervened with a force that was unknown at that time when the nearby volcanic island of Krakatau erupted. It produced tidal waves that devastated the coastal areas destroying much of Ujungkulon’s vegetation and northern coastlines.

Some insight into the impact of the tidal waves was recorded by a British ship 222 km south of

Ujungkulon on that day: “Encountered carcasses of animals including even those of tigers and about 150 human corpses…. beside enormous trunks of trees borne along by the current.

However, the re-growth was rapid and created lush new vegetation on which the browsing wildlife thrived. The first step toward the region becoming a national park began at the end of 19th century when the Ujungkulon Peninsula was establishing a reputation as a big game hunting area. During the following decade, there was no other region in all Java with as much game and so the trophy shooters came and animals were killed without limitations.

A group of conservationists and game hunters became concerned about the declining animal numbers and that some species were nearing extermination. This led in 1910 to the government’s first decree protecting some of the fauna, however the hunting continued.

Two years later, came the formation of the Netherlands Indies Society for the Protection of Nature. Their efforts had very little effect until 1921 when the society granted 300 sq. kilometres of the Ujungkulon Peninsula as a nature reserve.

Panaitan Island was also protected as a separated reserve.There was however no supervision and during the 1930’s hunting parties shot numerous animals.

In 1937, the status of the reserve was changed to the

Ujungkulong and

Panaitan Game Sanctuary and a small tract of land to the east of the Peninsula’s isthmus, together with

Peucang Island and

Handeuleum Islands, were included. All 42.120 hectares were then under the management of Director of Botanical Garden in Bogor.

Over the following years, the

Ujungkulon Game Reserve was closed to the public, a guard system was introduced and it appeared that

Ujungkulong and it’s wildlife had a promising future.

Then came the Second World War followed by Indonesia’s struggle to establish independence. The situation in

Ujungkulon Game Reserve deteriorated as management became difficult and many rhinos and other animals were once again being killed.

After the formation of the Republic of Indonesia, the

Ujungkulon –

Panaitan Island Game Reserve was again declared as a

Nature Reserve in 1958 and the coastal boundaries were extended 500 meters seaward. To the east of Ujungkulon Peninsula 20.000 hectares of the Gunung Honje Range also became nature reserves and the guarding was re-introduced to the region.

Ujung kulon officially became a

national park in 1992. In the same year, along with the

Krakatau Islands, the park shared the distinction of becoming Indonesia’s first

World Heritage (Natural) Site along with the Komodo Island. As with all national parks in Indonesia,

Ujung Kulon is managed by the

Republic of Indonesia.